Today my paper Do you have to pee? A Design Space for Intimate and Somatic Data will be presented at DIS 2019 in San Diego by a colleague from KTH as I am currently on parental leave with my four week old daughter. Would love to be at the conference presenting and discussing this work, but am more grateful for the conference’s flexibility and Vasiliki Tsaknaki’s assistance in the presentation of this paper while I am instead home in Sweden!

Since this research includes an autobiographic approach and a reflection on my positionality as a design researcher, both of which are critical to the work, the presentation I prepared included both video and audio recording of myself intermixed among a script for Vasiliki (which is why the script includes a mix of first and third person). It was definitely a new challenge rethinking how to make a presentation that included my own voice while using my colleague’s presence for audience engagement! Below is the full written script and slides, and the full paper (which won an honorable mention award!) is available here.

In this paper I investigate interaction design opportunities for and implications of leveraging intimate and somatic data to manage urination. This work is motivated by the increasing prevalence of data-driven technologies in intimate domains such as practices of bodily care. But prior to diving into the main content of the paper, I would like to first acknowledge my positionality. I am a female from North America and currently live in Northern Europe, whereby my cultural views on bodily excretion have heavily influenced what is and isn’t discussed, and who might be provoked and how. That being said, I hope for this work to invite much broader and inclusive future engagements for interaction design within the domain of bodily excretion.

Bodily excretion is an everyday metabolic process for all human beings. Yet despite its significance, it is often considered a taboo topic in design due to ethical concerns, individualistic practices, and a diversity of cultural norms. This means that interaction design challenges not only concern technology, but also interpersonal, societal, and cultural traditions and fears.

These challenges prompted the following research questions:

1) How might designers engage with intimate and unromantic bodily practices such as urination?

2) What opportunities exist for leveraging personal data to manage private toilet practices?

3) And when working with sensitive and somatic personal data, what should interaction designers consider regarding the externalization of internal sensations in private as well as social contexts?

To answer these questions, in the remainder of the presentation, we will focus on the detailing of a design space that contributes three considerations for designers, including:

– the labeling of somatic data,

– the actuating of bodily experiences, and

– the scaling of intimate interactions.

But before jumping into this design space, this work is positioned at the intersection of designing with data, bodily care and maintenance, and technologies for human waste.

Designing with data is not a new practice, and in the paper Karey gives a variety of examples – but here we highlight a designer’s role and agency in shaping data when bringing it into a design space.

There is a growing body of work within HCI design research investigating bodily care and maintenance, and in particular a deepened understanding of our felt bodies as seen in somaesthetic design and women’s health. Karey draws heavily upon design research that challenges bodily taboos and inattention.

And lastly, the removal of bodily excretion has a long history with technology, which includes the modern toilet and sewage infrastructures. But most relevant to this work is that of which explores social boundaries, bio-surveillance, and gender narratives.

To open a design space, three design methods were engaged with, each building upon the former. These included:

– A critique of market exemplars,

– The design of three conceptual provocations, and

– Autobiographical data-gathering and labeling of urinary routines.

I will next briefly introduce each method and expand upon the results.

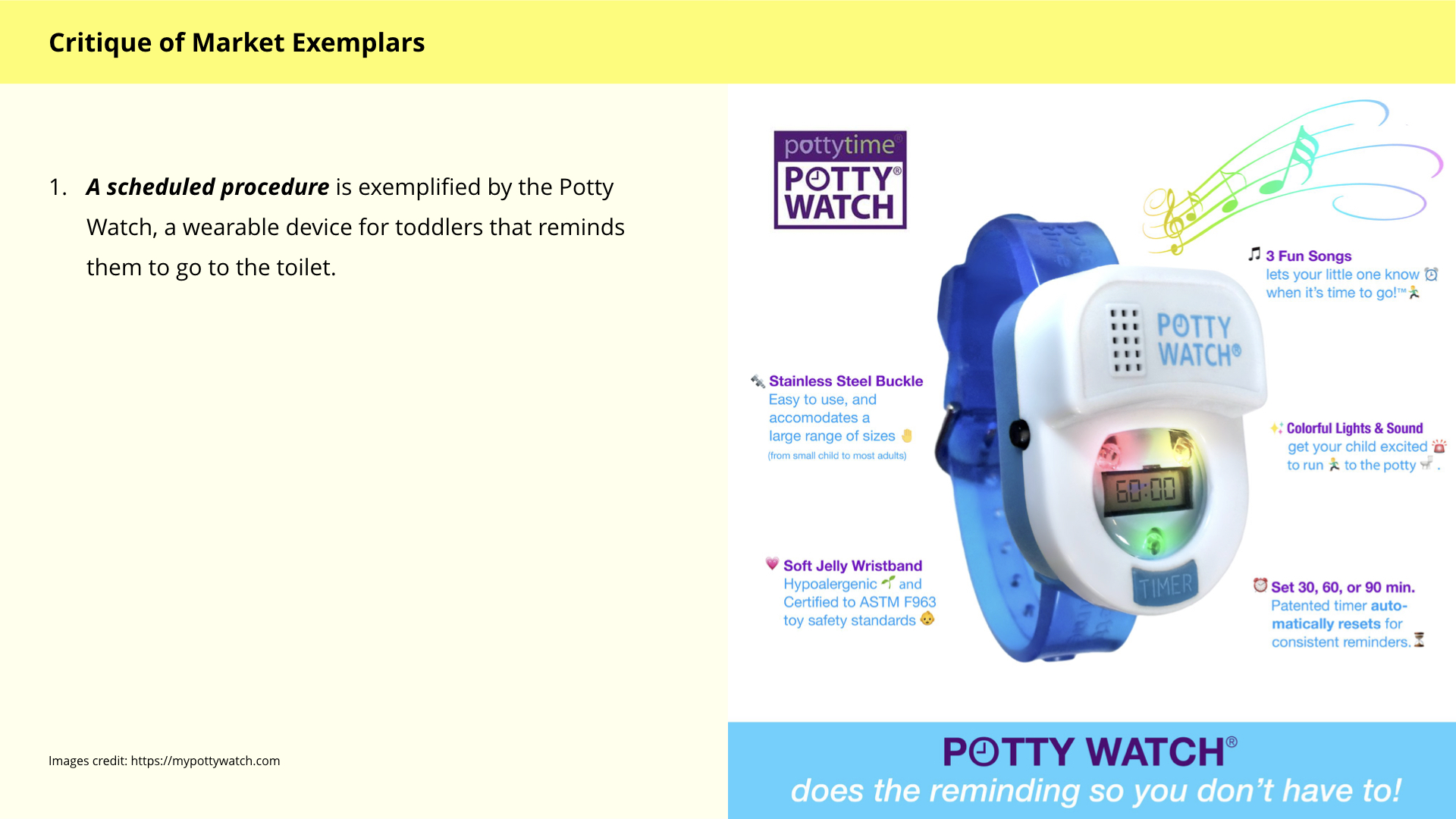

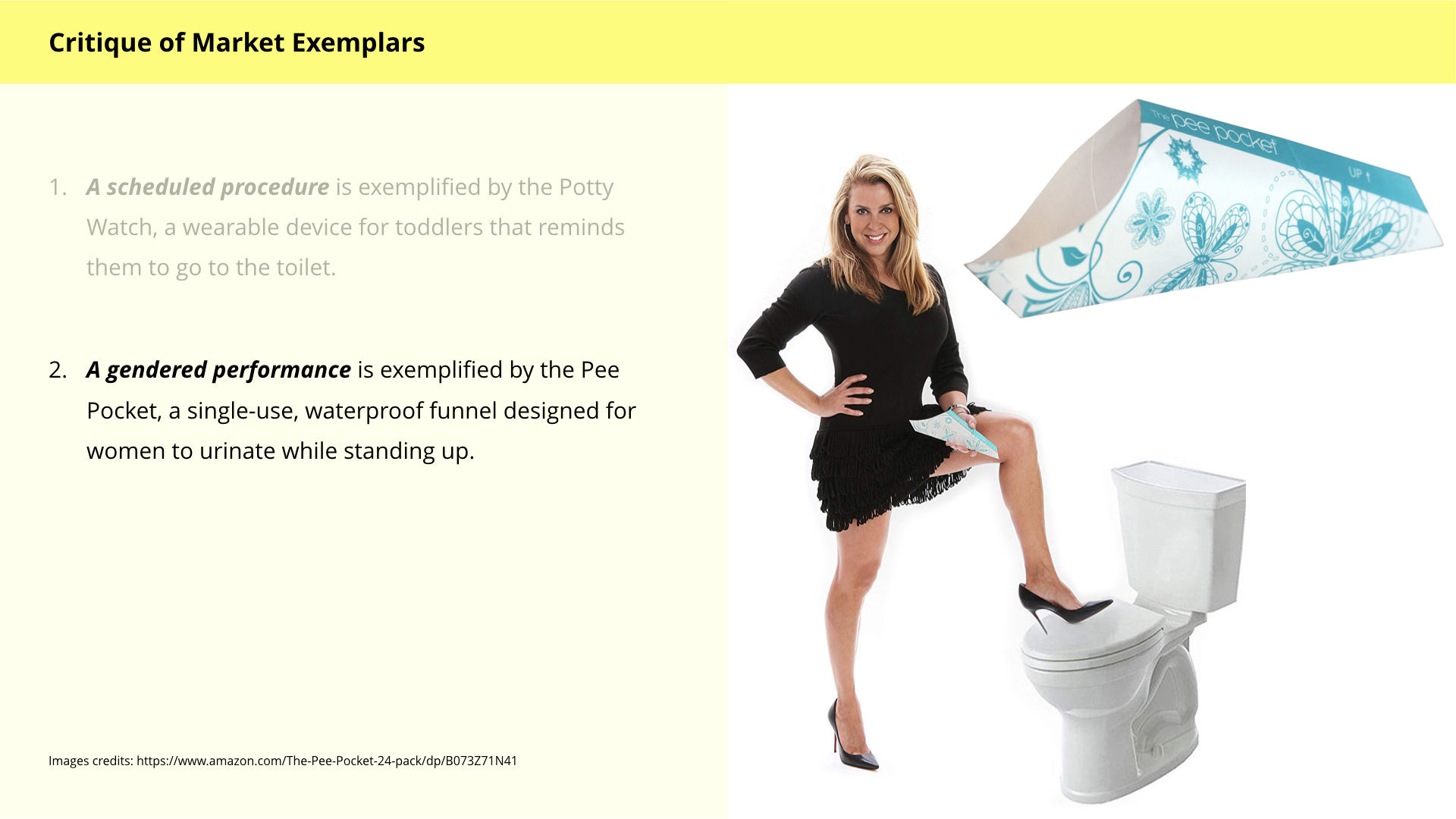

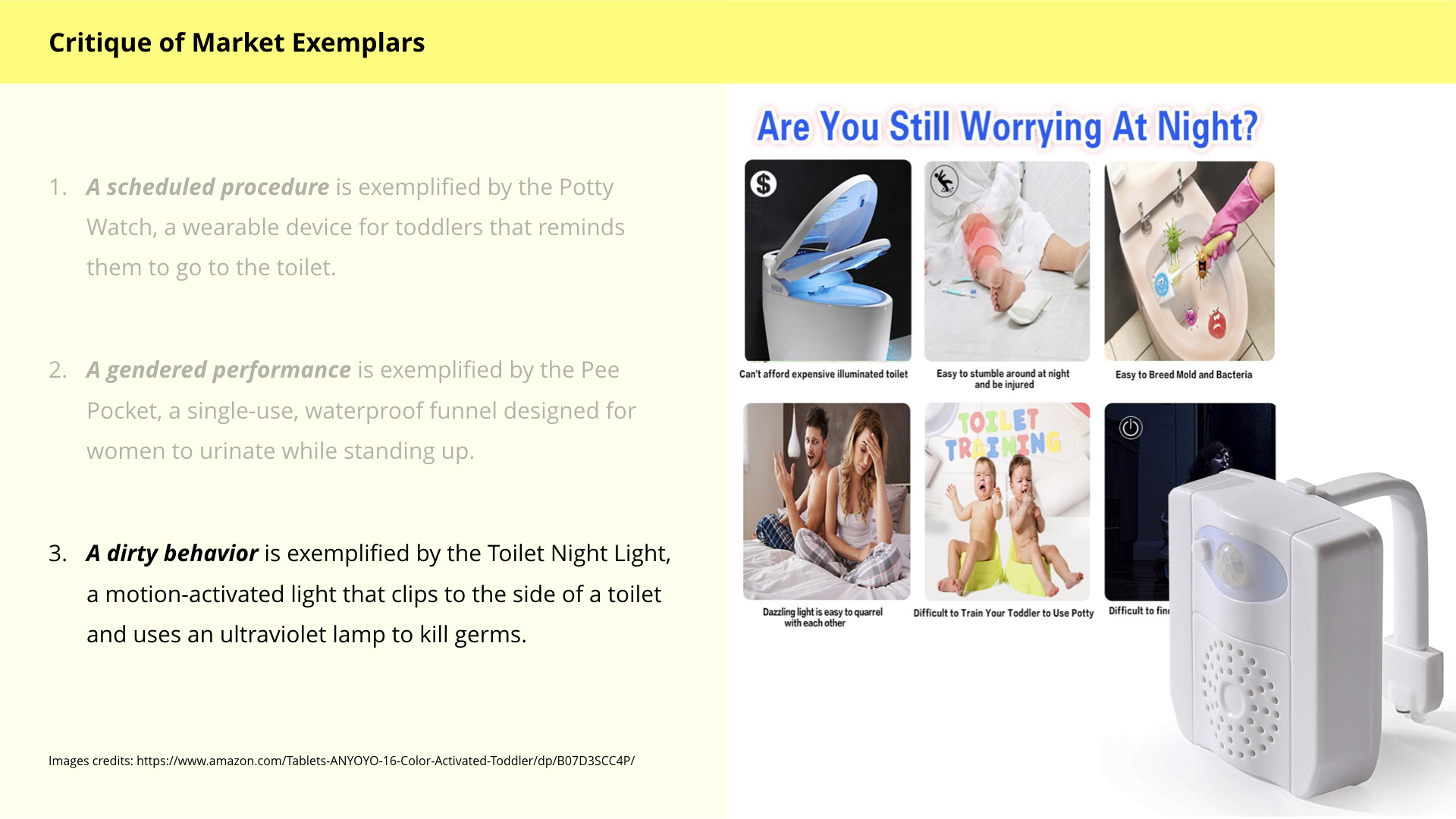

The first method, a critique of market products, was chosen due to commercial product development that prompts questions regarding what these products might reveal about societal perspectives on the management of excretion. Three themes were identified from the critique – regarding the how, who and where of urination – and used for subsequent ideation.

The first theme that emerged from my critique on the how of urination was a scheduled procedure, which is exemplified by The Potty Watch. The Potty Watch is a wearable device for toddlers that reminds them to go to the toilet through a pre-set timer. I perceived the underlying messages of the product to be that urination occurs on command and technological devices can replace the recognition of internal bodily sensations and urges.

The second theme that emerged from my critique on the who of urination was a gendered performance, which is exemplified by the Pee Pocket. The Pee Pocket is a single-use, waterproof funnel designed for women to urinate standing up. Due to marketing that accentuates portability and discreetness while idealizing speed, convenience, and comfort in standing, I perceived the the underlying message to be that it is empowering for vulnerable women if they can imitate a man to urinate.

The third theme that emerged from my critique on the where of urination was a dirty behavior, which is exemplified by the Toilet Night Light. The Toilet Night Light is a motion-activated light that uses an ultraviolet lamp to kill germs. I perceived the underlying message to be that toilets, the spaces they occupy, and the behaviors that take place are dangerous and should be feared as a result of contamination, conflict, and suffering.

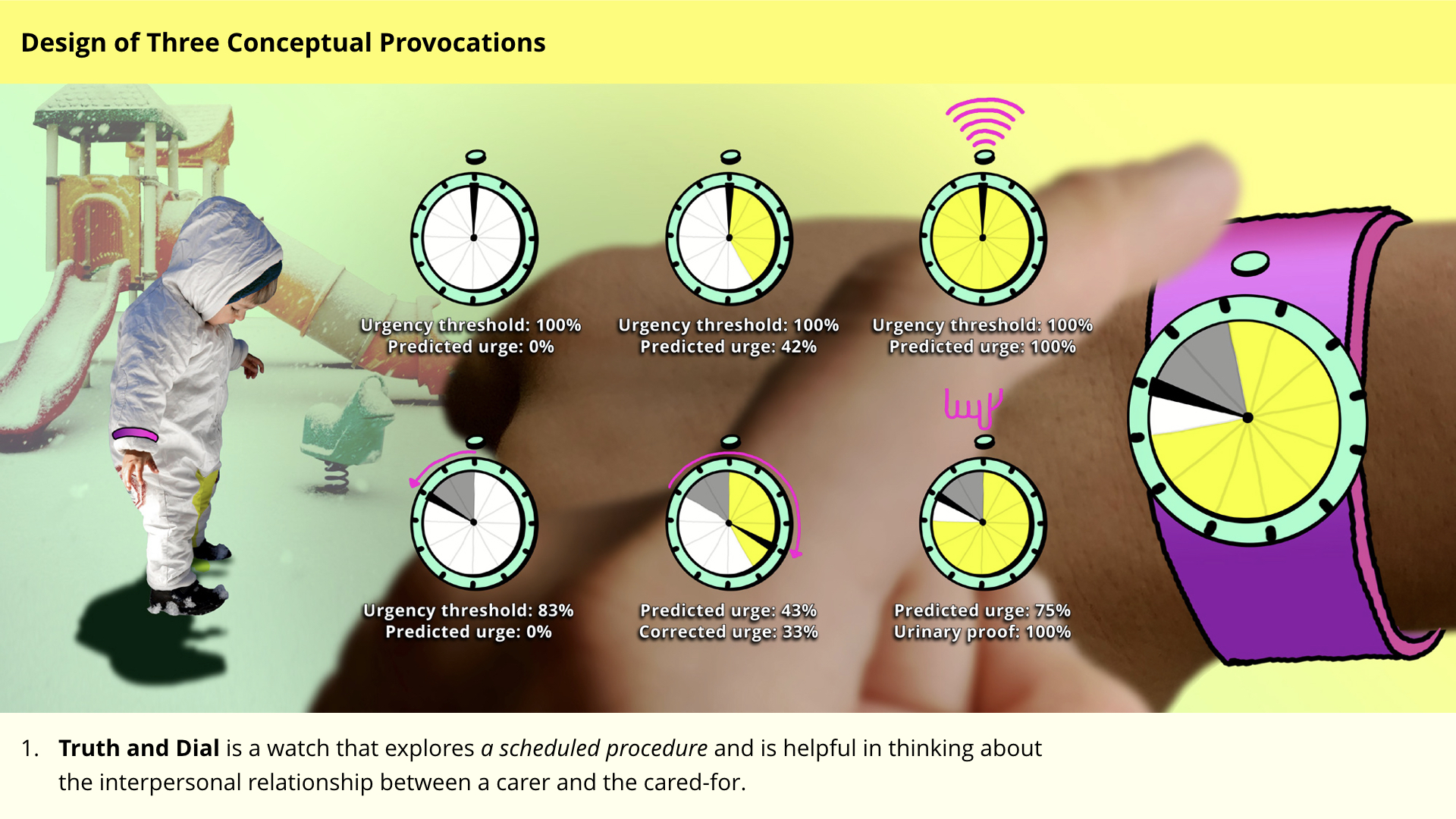

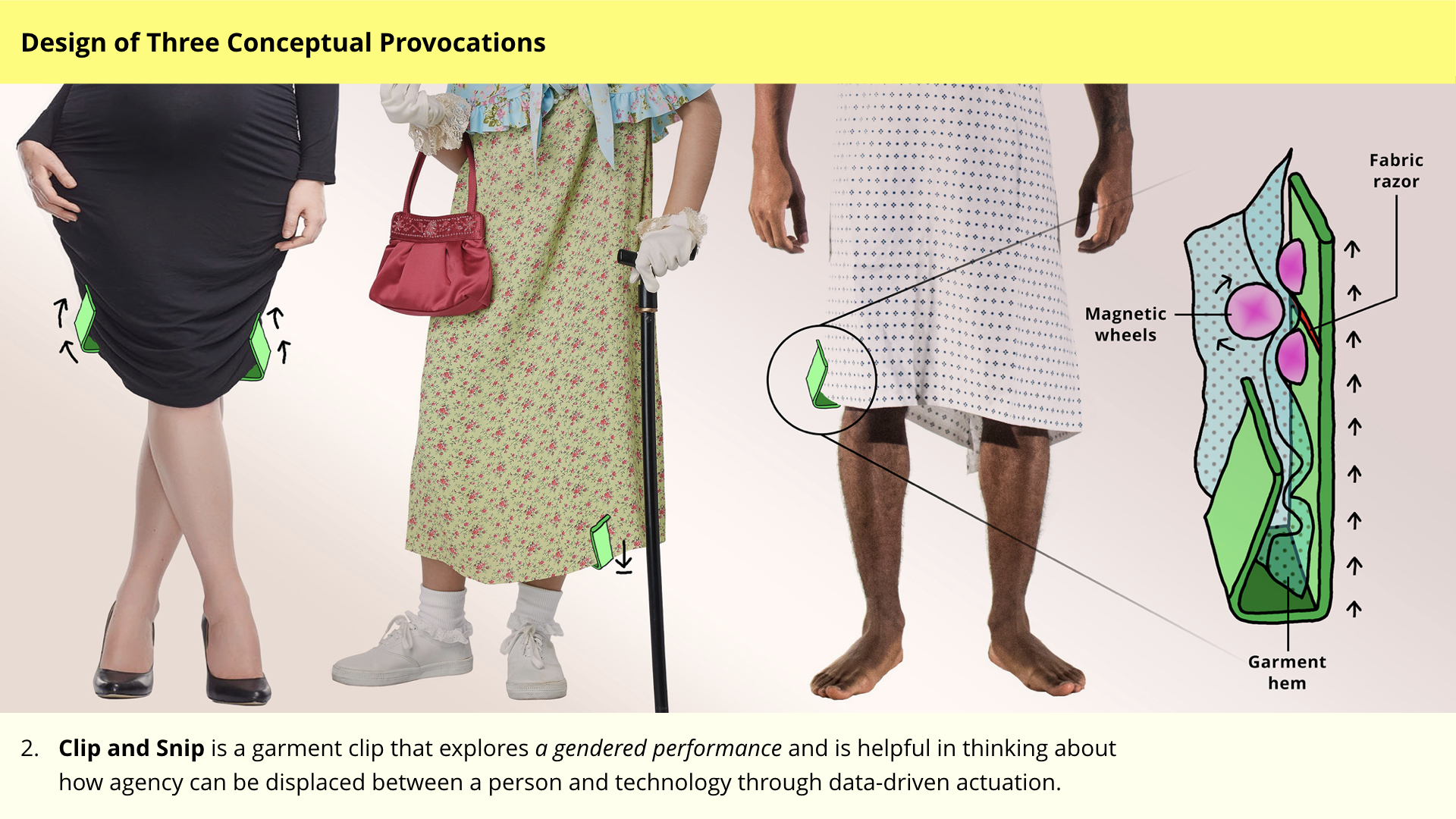

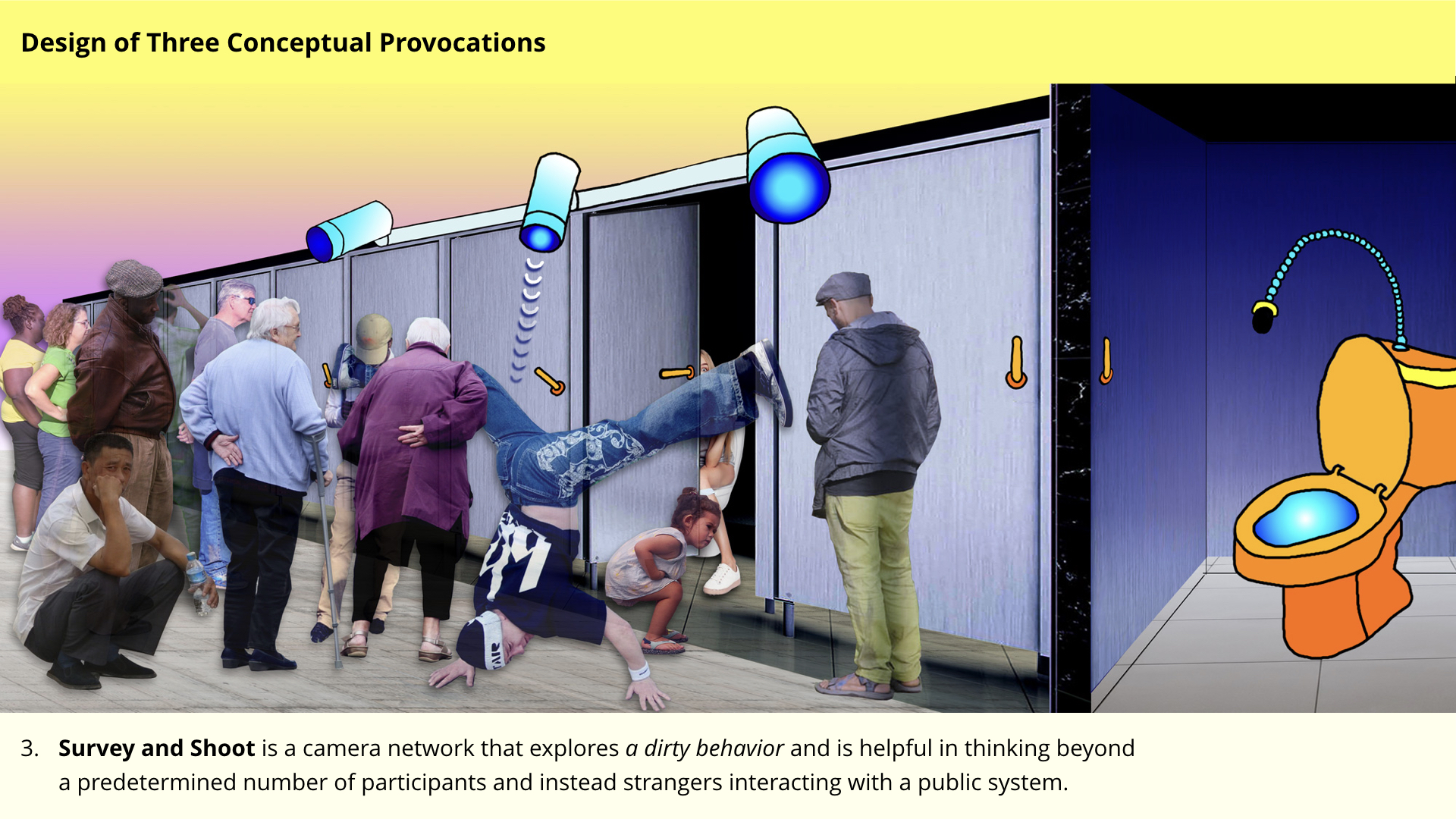

The second method was the design of three conceptual provocations that predict when and how badly one might need to urinate. This functionality was chosen for its potential benefits for people who cannot manage their own excretion, and its reliance of data-driven inference-making to surface interaction design challenges. Each provocation is grounded in a theme from the critique and is meant to be an exaggeration of a solution to prompt discussion.

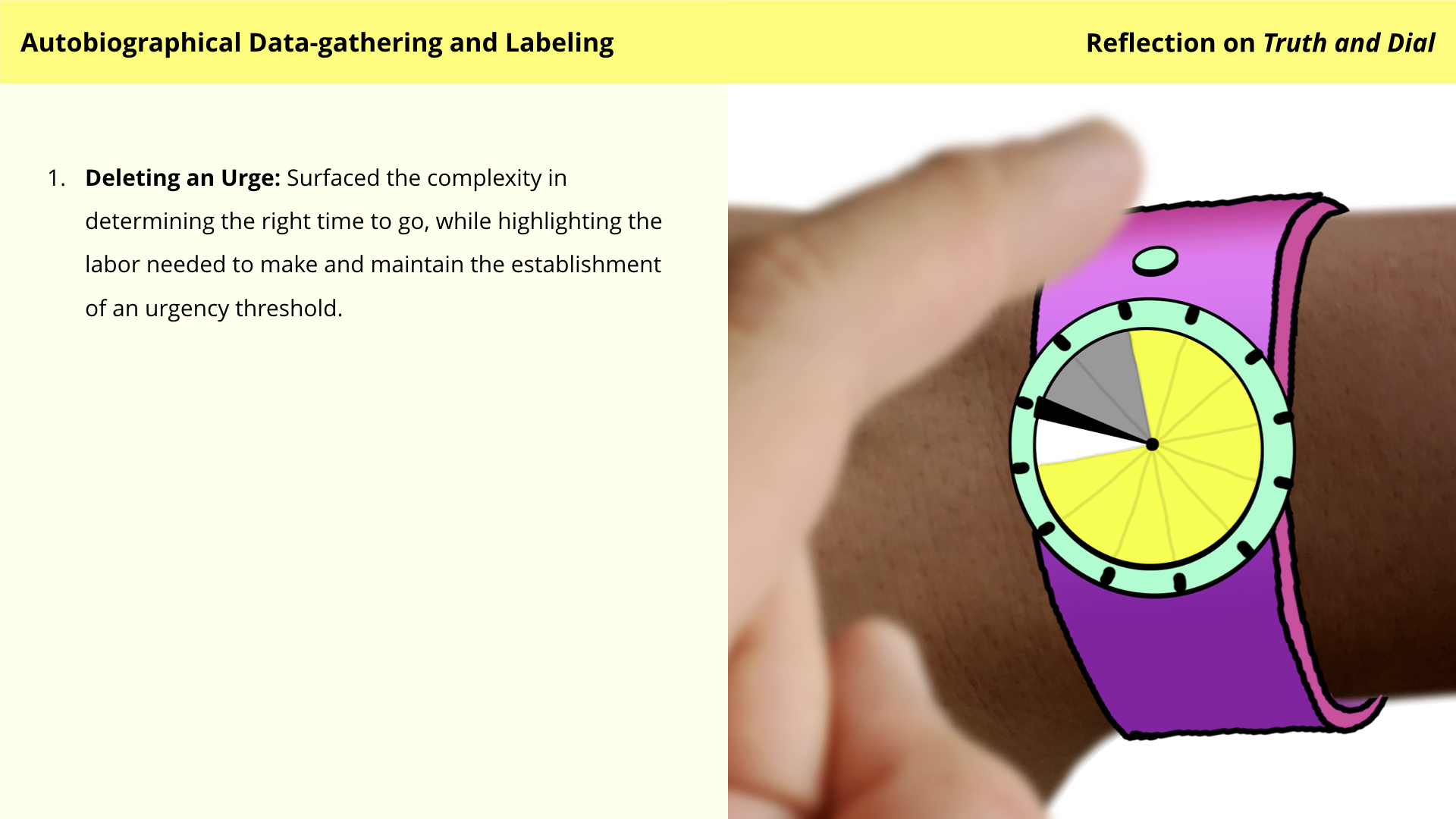

The first design provocation – Truth and Dial – is a watch that explores a scheduled procedure and is helpful in thinking about the interpersonal relationship between a carer and the cared-for. The watch is designed to be worn by a guardian to manage the urinary urge of a child. The yellow sections of the interface gradually fill up as a predicted urge to urinate increases. A black dial on the interface is used to set an “urgency threshold” to notify the guardian via an audio alarm when the urge reaches a particular level. The alarm is turned off by pushing a “peed” button, which indicates to the system that the child has urinated. The watch is meant to be provocative by highlighting interpersonal power imbalances and the social exposure of care-taking.

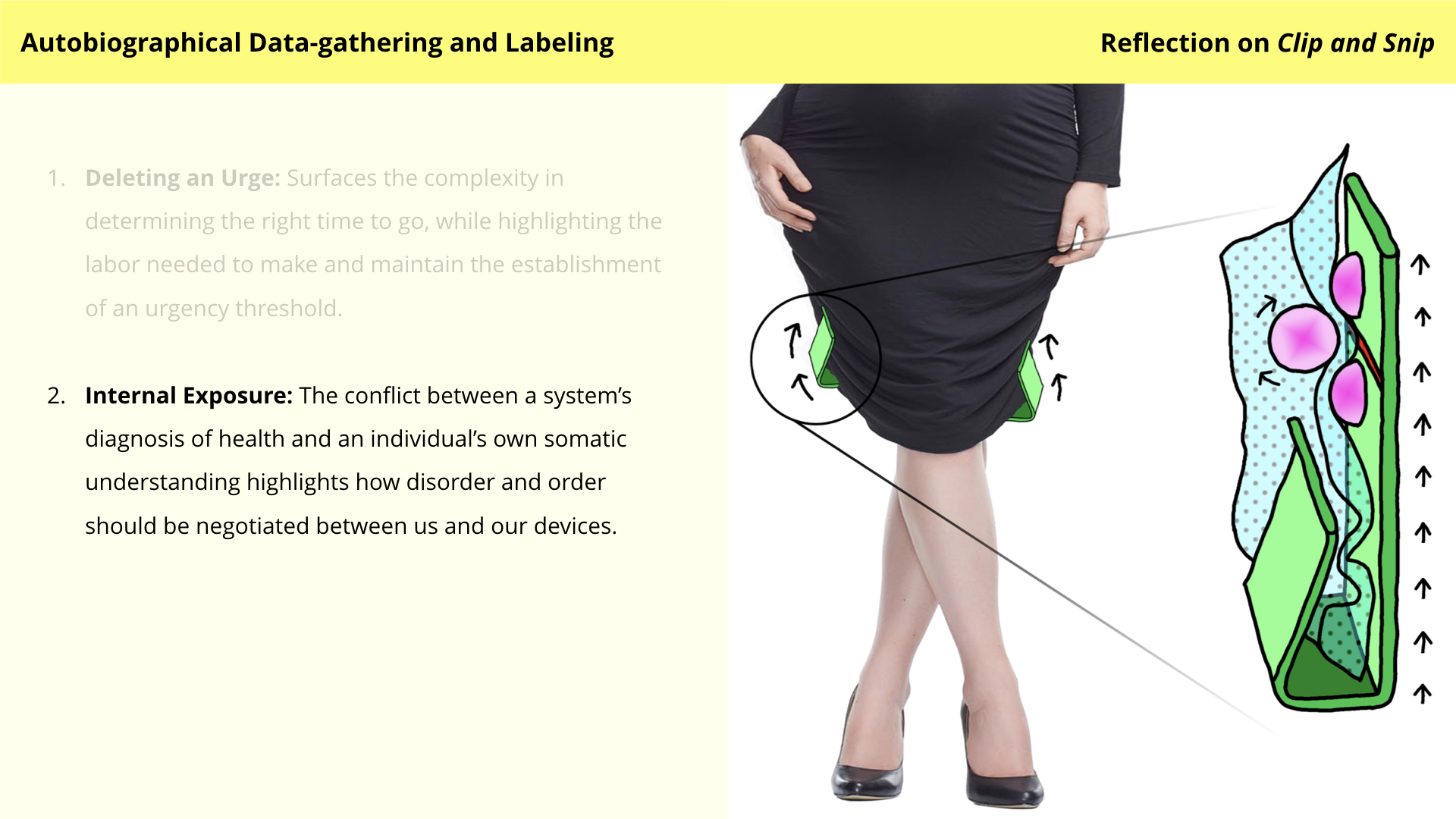

The second design provocation – Clip and Snip – is a garment clip that explores a gendered performance and is helpful in thinking about how agency can be displaced between a person and technology through data-driven actuation. The clip is designed to be attached to the bottom of a hem. Magnetic wheels secure it to the fabric and sensors form a representation of the urinary urge of the wearer. As the detected urge increases, the magnetic wheels gradually move up the garment, causing the hem to rise and thus making it easier to urinate. If the hem is pulled down to correct the prediction too many times or if an urge is not addressed in a healthy timeframe, the system uses a fabric razor to clip off the bottom of the garment. The clip is meant to be provocative by foregrounding experiential dilemmas and challenges of agency with technology that is meant to assist vulnerable users.

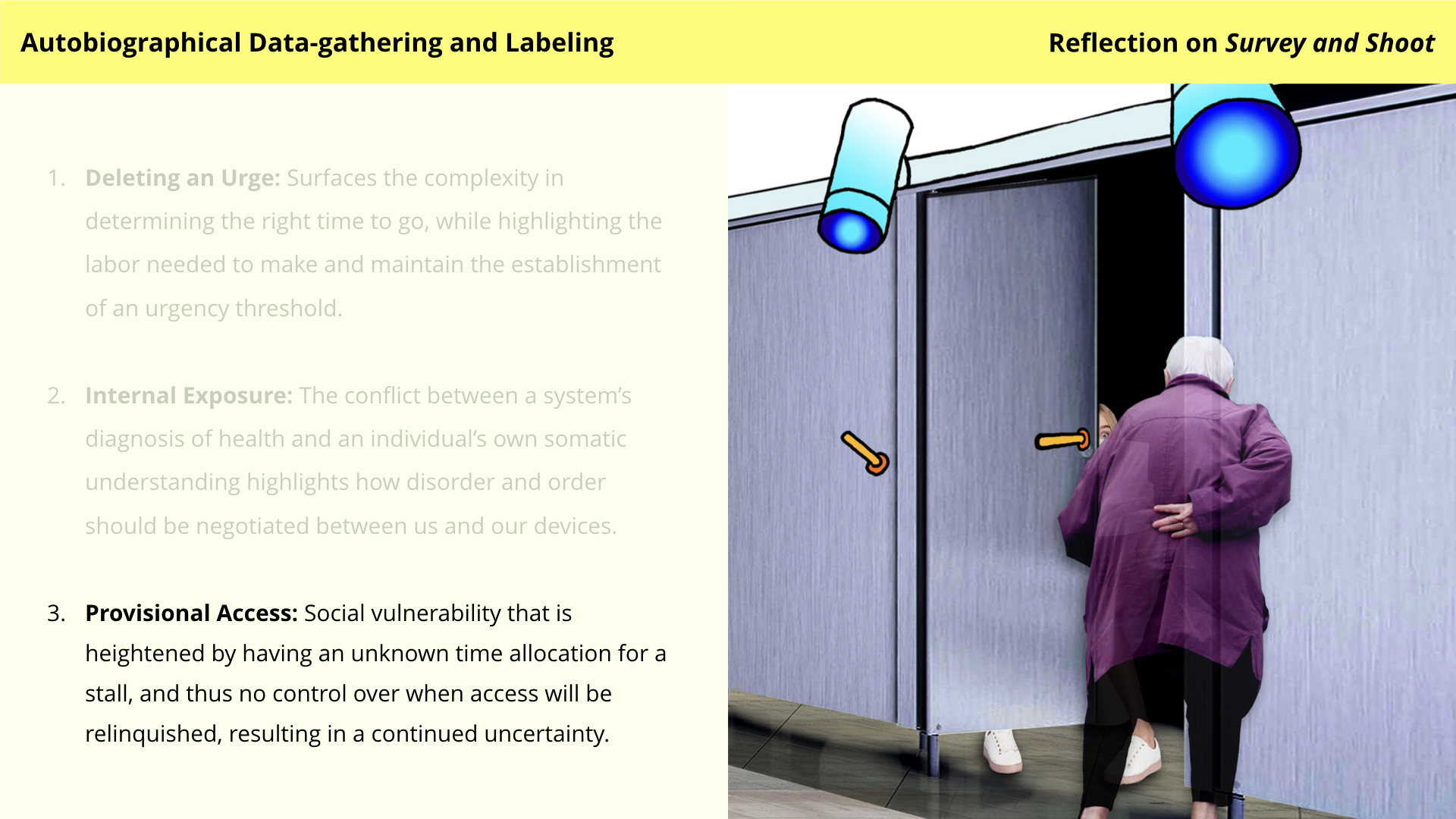

The third design provocation – Survey and Shoot – is a camera network that explores a dirty behavior and is helpful in thinking beyond a predetermined number of participants and instead strangers interacting with a public system. The camera network uses computer vision to form representations of urinary urges of people in a public space to democratically grant facility access. When a toilet stall is available, the system notifies the chosen person by shooting him or her with an air haptic, also known as a “poof”. The amount of time an individual has in a stall is dependent upon their detected urge. The camera network is meant to be provocative regarding the use of data-driven technology at scale to govern access in the prevention of deviant behavior.

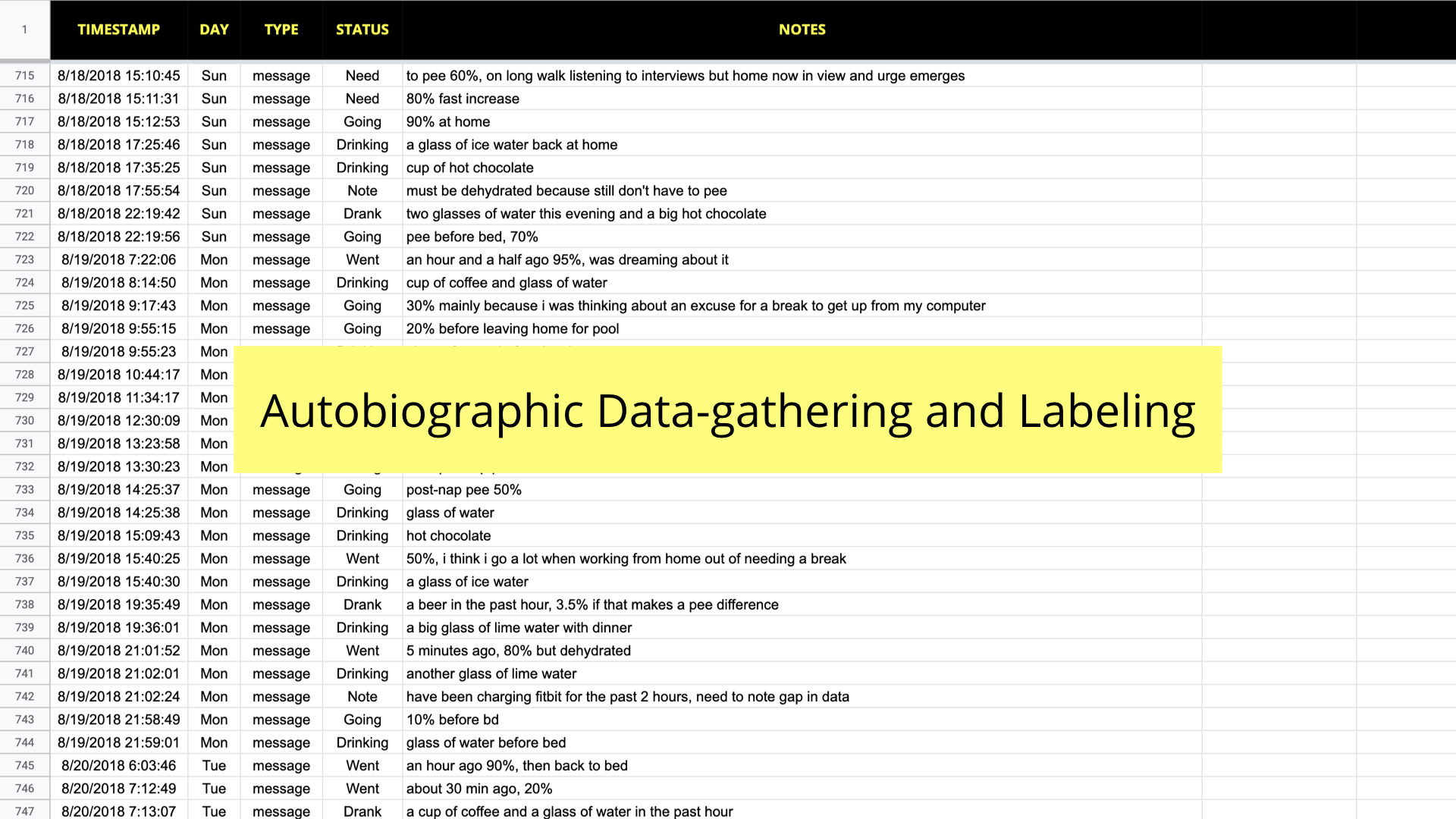

The third and final method was autobiographic data-gathering and labeling of urinary routines over a six-month time period. This approach was chosen to defamiliarize with the automated perceptions of urination. Tracking was a simple technical setup whereby Karey messaged her urinary habits to a chat application. Each message was automatically forwarded to a spreadsheet with the contents sorted by time, day, type, status, and notes (as seen in the image). The resulting insights were used as a method of reflection on each of the three conceptual provocations. We will next give one example reflection on each

One of the first reflections was the ease of which I previously “deleted” going to the toilet, which drew attention to how much unacknowledged time and coordination contributes to inserting urination into daily routines. For example, the idea of a “security pee” emerged to describe going to the toilet despite not needing to urinate urgently, but just in case a facility might not be available another time soon. In regards to Truth and Dial, this reflection surfaced the complexity of past and future events in determining the right time to go, while highlighting the labor needed to make and maintain the establishment of an urgency threshold.

While visiting a friend abroad, we happened to notice that our urine was the same peculiar shade of yellow. As one’s urine can reveal signs of health or lifestyle, our sharing of this information made my urine feel more “normal.” This relates to an intimacy of knowing one’s own body, and the potential shame if it does not abide by cultural norms. Although Clip and Snip only claims to communicate an urge, when considering the clipping of the hem, the conflict between a system’s diagnosis of health and an individual’s own somatic understanding, highlights how disorder and order should be negotiated between us and our devices.

Opening a door to encounter a stall in use, or having a stranger try to open a locked door on myself, were not uncommon occurrences. This lead me to think about the sociality of a somatic experience, by which potential encounters impact whether a bodily excretion is enjoyable or can even occur at all. In Survey and Shoot, provisional access contributes to social vulnerability by having an unknown or unexplained time allocation for a stall, and thus no control over when access will be relinquished.

So what can interaction designers learn from this design space? From the individual outcomes and culmination of the three methods, in the paper I contribute three considerations for designers.

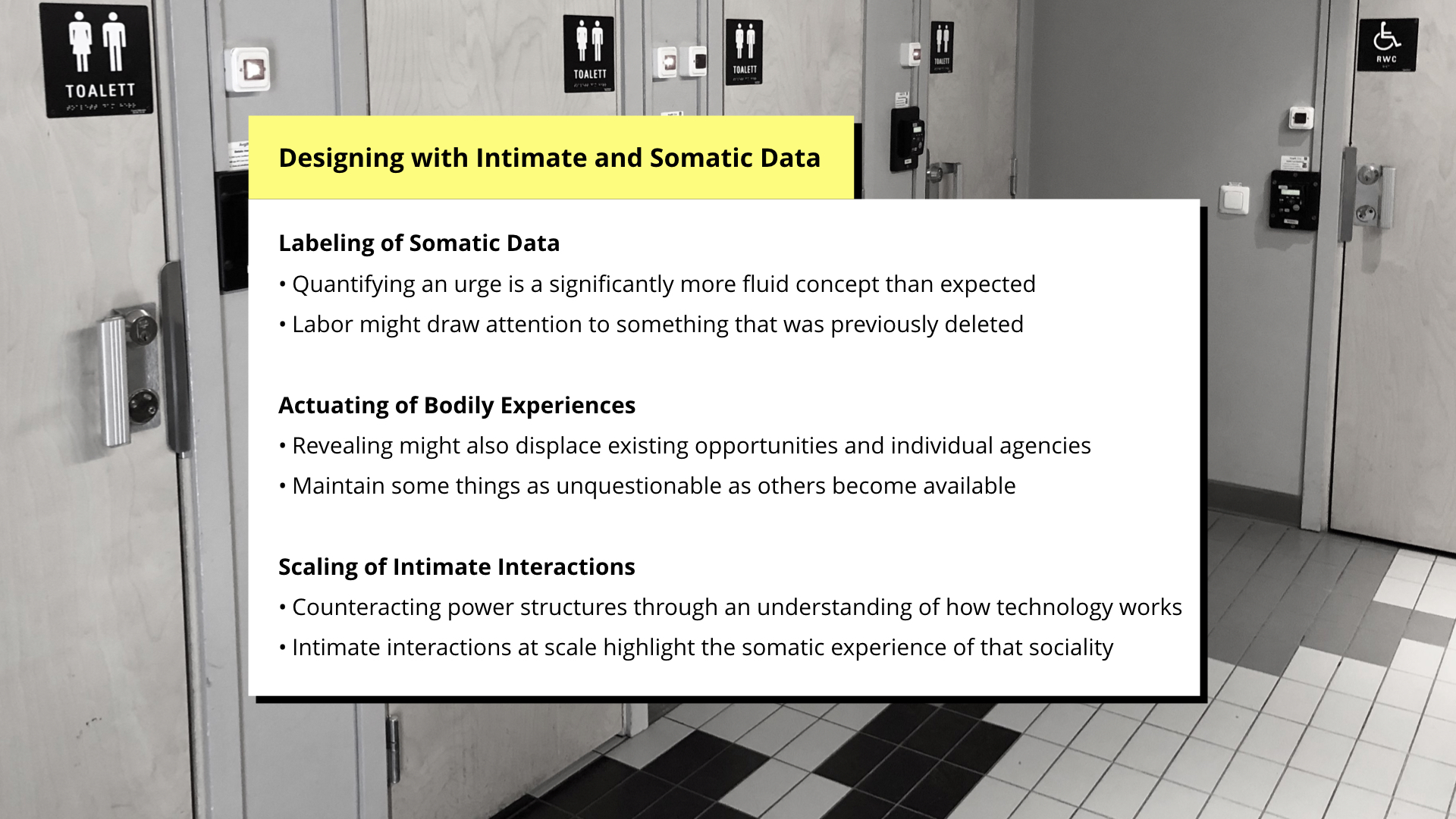

The first is the labeling of somatic data. As similarly seen in affective interaction, there is a difficulty in resolving conflicts between what is sensed by the system and what is sensed by the self. Quantifying an urge is a significantly more fluid concept than expected and opens further questions regarding how to design with data and present it in a meaningful way when nothing is stable. Furthermore, the labor involved in labeling might also implicitly draw attention to something that was previously deleted.

The second is the actuating of bodily experiences. Through the transformation of somatic interpretations into the actuation of a device, something previously implicit or unnoticed is made explicit and recognizable. While this revealing might be empowering, it might also displace existing opportunities and individual agencies. Thus, designers might consider how to maintain some things as unquestionable as others become available through device actuation.

The third is the scaling of intimate interactions. Design and power is not a new topic in HCI, and as data-driven devices participate in public services, the knowledge of intimate data contributes to transformations of power and access. This also includes how power structures might be counteracted through an understanding of how such technology works. Furthermore, intimate interactions at scale and in public spaces highlight the somatic experience of this sociality.

I would like to conclude the presentation with reflections on my methodology and positionality.

While there is significant research on bodily excretion, such as the UK-based Around the Toilet project, in addition to drawing attention to these efforts, I would like to offer my methodological process, and in particular my autobiographical approach, as a way to see what was previously obscured within my own design practice. My own future work includes inviting other perspectives through the continued development of the three provocations.

Also, although I disclosed my positionality at the beginning of the presentation, as mentioned in the paper, during the design process I became pregnant, at the time of writing this paper was 5 months pregnant, and by the time you are watching this recording I am expected to have a 4 week old baby. These life changes challenged my own situated interpretations of this work, whereby the concept Truth and Dial became less provocative and instead appealing. This more recent interpretation illustrates how positionality can change, and so as a Research through Design contribution, I consider my own intentions one fluid perspective of many.

Lastly, I would like to give a special thanks to Vasiliki, Ylva, Barry, Airi, and Marie Louise for their valuable feedback and support of this work!